“The soul that is full loathes honey, but to a hungry soul, any bitter thing is sweet.”

We don’t know who authored this little proverb (which comes from the Bible’s Book of Proverbs), but you’ve got to hand it to whoever it was: he was a keen observer of human psychology. Hunger, he noticed, doesn’t simply motivate our souls to get off the couch and go find something to eat; instead, it changes our psychological relationship to food. When we’re hungry, he noted, we lower our standards: even the nasty bits are magically transformed into delicacies.

Our quality standards will sink so low when we’re hungry, in fact, that we’re even willing to eat foods that are bitter. Ordinarily, humans tend to dislike things that taste bitter because bitterness often indicates that the food we’re eating (it’s typically a plant) contains toxins whose very function is to prevent us from eating it: The plants don’t want to be eaten, and the bitter taste deters us from doing exactly that.* Hunger says, “Look. You’re starving. What difference is a little bit of plant toxin going to make? Eat that bitter thing today. You can do your detox diet tomorrow.”

What exactly is hunger? It goes without saying that hunger is a psychological state that deals with a discrete problem of survival and reproduction—your body is low on the energy it needs to keep itself running, and you won’t stay alive if your body stops running, and you can’t reproduce if you aren’t alive. Fine, but what kind of thing is it? Although many emotion researchers have been coy about saying it out loud, hunger is starting to look an awful lot like an emotion—at least on the view of emotions that evolutionary psychologists tend to favor.

Articulating a widely accepted evolutionary-psychology view of emotions, the psychologists Laith al-Shawaf and David Lewis defined emotions as “coordinating mechanisms whose evolved function is to coordinate a variety of programs in the mind and body in the service of solving a specific adaptive problem.” As examples of prototypical emotions, Al-Shawaf and Lewis point to fear (which directs a variety of physiological, behavioral, and cognitive responses that help to keep us away from dangerous things), disgust (which directs a variety of physiological, behavioral, and cognitive responses that help to keep us away from infectious things), and sexual arousal (which directs a variety of physiological, behavioral, and cognitive responses that help to direct us, as they put it, toward “advantageous mating opportunity[ies].”

So why not count hunger among them? Well, why not indeed? In another paper, Laith posited as much when he defined hunger as “a mechanism that coordinates the activity of psychological processes in the service of solving the adaptive problem of acquiring food.” And here, I think he was right on the money: If all things that are “coordinating mechanisms whose evolved function is to coordinate a variety of programs in the mind and body in the service of solving a specific adaptive problem,” and hunger is “a mechanism that coordinates the activity of psychological processes in the service of solving the adaptive problem of acquiring food,” then hunger is an emotion, is it not?

Although the evolutionary psychologist’s view that hunger is an emotion puts them (I think) in the minority of emotion researchers, there are other scientists who think of hunger in a very similar manner. The neuroscientist E.T. Rolls has conceptualized hunger as what neuroscientists call a gate. When the hunger gate senses that the body is in a depleted nutritional state, it turns the bare sensory information that we pick up from the tastes, sights, smells, and textures of foods into behavioral mandates. When the gate is closed, “the soul loathes honey.” When it’s open, “any bitter thing is sweet.” Indeed, researchers have now found the gene-regulator that opens and closes the hunger gate in the roundworm C. elegans (which is probably the most studied organism in the history of biology). It’s plausible that a similar molecular signaling system functions as a hunger gate for humans as well.

What psychological and physiological “programs” does hunger coordinate? Probably quite a few. Laith provides a long list of hunger’s miraculous powers (including some that are supported by existing research and others that are more speculative, requiring further research). Hunger, he ventures, influences perception (the bare sensory properties of foods, such as their sights and smells, lead us, gate-style, to craving or pleasure rather than indifference), attention (we notice food-related stimuli that we otherwise would ignore), problem-solving (we automatically start sorting through our options for finding food) categorization (we begin to automatically categorize things in the world as either “food” or “not food”), and memory (we find it easier to recall the locations of food items).

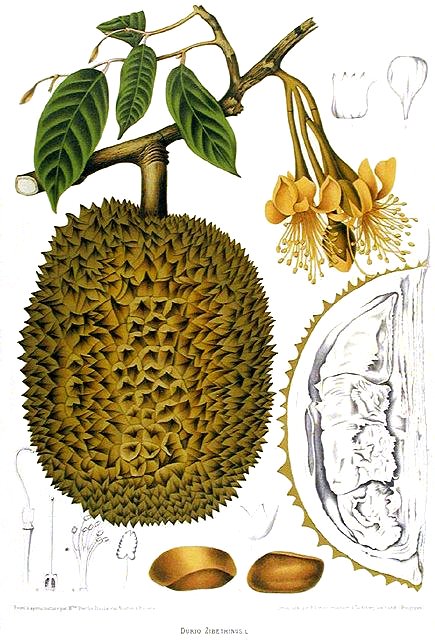

Support for these hypotheses is rolling in. In research that came out recently, scientists found that hunger makes food odors more attractive. Another team of researchers recently found that hunger makes Dutch undergraduate students more willing to eat novel foods such as African cucumber, fried snake, crocodile meat, kangaroo thigh, and the notoriously tastes-delicious-but-smells-like-sewage fruit known as the durian.

Effects like these bear witness to hunger’s long reach into our bodies, our thoughts, our feelings, and our behaviors. If the aphorist who wrote Proverbs 27:7 were alive today, and he could spare a day from scrawling down universal human wisdom in order to read up on the evolutionary psychology of hunger, perhaps he would write a follow-up proverb:

“Hunger gates incoming food-related sensory information into physiological responses, psychological states, and behavioral propensities that evolved for the function of re-uniting our bodies with nutrients.”

Or not. Either way, it’s fun to imagine that guy, probably wearing a flowing robe or something, hunched over his computer while he scrolls through Google Scholar with one hand and grips a massive, stinky durian with the other.

~

*Yes, as a matter of fact; I am aware that coffee, collards, and cocoa are bitter, along with many other things that are nice to eat and drink. There may be an adaptive reason why we’re attracted to bitterness in some cases—and it turns out those cases are the exceptions that prove the rule. But that’s a story for another day.